BryanMaloney

Premium Member

Most of us are already aware of the Masonic Service Association of North America's (MASANA) informative date. Web sites and publications have referred to it in order to show the decline of membership for Freemasonry in the USA. I have also posted on this data, specifically to point out how interpretations change depending on how deeply one delves. First, the simplest look at the data is the image that most people who look at the issue of Freemasonry membership are familiar with.

The total number of Master Masons (Fig. 1) appears to show that Freemasonry in the USA reached a high point in 1959 and has been declining ever since. Such a presentation, although popular, is quite deceptive, since the US population was also increasing at a great rate in the decades immediately after the Second World War.

Thus, when adjusting for population (Fig. 2), the result presents a different picture. Freemasonry had its highest population-adjusted membership (within the years surveyed) in 1927, with a temporary reversal of losses that ended in 1959 but never made its way back up to former levels. This difference between raw counts and population-adjusted counts may, in and of itself, be important, since it suggests that nostalgia for “glory days†of the 1950s may actually be ill-founded. What is more informative than counts if we are looking at membership trends is how membership changes. That is, the slope of the membership curve.

Differentiating the population-adjusted figures finds rates of change (slopes of the curve) in membership (Fig. 3). The differentiation result is particularly informative.

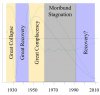

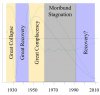

The various inflections, combined with more raw membership data, suggest the possibility of dividing 20th and early 21st century Freemasonry in the USA into five periods (Fig. 4). The first of these I call the "Great Collapse". Freemasonry in the USA had its fastest rate of loss, without exception, at least for the period covered. This was followed by the "Great Recovery", in which the losses of the Great Collapse began to be reversed almost as fast as they had occurred. The next period I call the "Great Complacency". On the surface, merely looking at raw counts of Master Masons, things looked great. There was nothing to worry about. However, looking a little deeper showed that Freemasonry's penetration into the population of the USA as a whole had never returned to pre-Great Depression levels, and looking at the rates of change for Master Masons per population showed that much of the "golden age" was actually a time of loss of growth that linearly slid into decline almost as extreme as the decline of the Great Collapse. The long period after the Great Complacency I call "Moribund Stagnation". That is, while Freemasonry was in a state of decline, the rate of decline was at least constant instead of getting progressively worse, year after year. Finally, the possibility of a "Recovery?" may be present in the data. Although counts of Master Masons and of Master Masons per population still drop annually, the rate at which they drop has been growing less severe.

To look at these phases in more detail, It is true that freemasonry in the USA has been in unremitting membership decline (slope less than zero) for several decades, but actual decline (slope less than zero) in terms of Master Masons vs. population began in 1955, four years before the highest raw count of Master Masons was achieved. What is also noteworthy are four inflection points in the slopes, occuring at 1933, 1946, 1961, and 1993. In 1933, the Great Decline reversed itself. Matters improved from 1933 to 1946, when membership decline rapidly slowed and then reversed to growth. However, in 1946, the trend underwent another drastic reversal.

The year 1946 had the greatest increase of Master Masons, but things went downhill from that point, onward. The trend sharply declined, even if the numbers and population-adjusted numbers still increased. In essence, the “glory days†of 20th century Freemasonry were actually little more than a few years, 1941–1946, when numbers were growing and the growth trend was not plummeting. What is interesting is that this does not mesh well with many current hypotheses to explain changes in membership. The conventional explanation for membership drops and gains in Freemasonry of the early 20th century has been that the Great Depression drove men away from the Craft, and this was reversed when GIs coming home after the war sought to continue their military comaraderie. In actuality, watever early-century decline in Masonic membership began before the stock market crash of 1929 and had reversed itself after 1933. Freemasonry had already been recovering for several years before the USA entered the Second World War. Growth was almost explosive throughout the war, but the the trend catastrophically reversed by 1946. Residual effect produced gains in both numbers and population-adjusted numbers, but growth had begun to decline before the 1950s had even started and slipped into decline by 1955. Thus, whatever had driven the amazing resurgence of American Freemasonry in the middle of the 20th century was already half a decade gone when the 1950s had started.

In 1961, the precipitous collapse of Freemasonry essentially ended, replaced by a relatively constant state of decline, in which the Craft essentially coasted downhill. It would not be unreasonable to propose that nothing done between 1961 and 1993 had any significant effect for good or ill on Craft participation. Freemasonry in the USA had settled into a state of steady decay, as constant as a radioactive half-life. Around 1993, the trend appears to have once again reversed, although far more moderately than before. Instead of the constant rate of loss that had been the regime for the previous generation, nationwide rate of loss of Master Masons (population adjusted) began to ease. By 2010, the rate of loss had dropped to about one third the loss rate of the stagnation generation (1961–1993).

Conventional models of “what worked†for Freemasonry in the 20th century may very well be entirely wrong. First, the period of greatest growth began before the USA had entered the Second World War. This period ended a year after the war. By the time the majority of GI Generation Master Masons had been elevated, decline had already set in, even if it was not superficially apparent. The 1950s was not a golden age, it was merely gilded. While Freemasonry became “largerâ€, under the surface it was drastically already in decline. By the time the 1960s appeared, the Craft in the USA had essentially entered a holding pattern, sustained in a constant downward spiral.

Whatever brought men into Freemasonry in the early 20th century was already in place in the USA before any enforced camaraderie of the Second World War. Large numbers of men were also inducted into the military for the Korean and Viet Nam conflicts, but these eras did not see even tiny spikes in Master Masons. The “GI hypothesis†simply does not fit deeper analysis of the data. It is not doubted that shared hardship can create fraternity. However, it is also an unfortunately common presumption that nothing in history is important except warfare. Thus, we are taught to classify American history by our wars, as if nothing else important ever happens in the USA other than warfare.

Shared American hardship in the early 20th century did not begin in December of 1941. An even deeper shared trauma began in 1929. This refers, of course, to the Great Depression. This was a shared experience that overturned our entire culture and led to mass cooperative efforts that essentially set the stage for what the USA was able to do during the Second World War. Thus, in opposition to the “GI hypothesisâ€, a more prosaic social and economic hypothesis could be considered. The year 1933 marks the low point of the Great Depression in the USA. In terms of both gross domestic product per person, employment, and real-dollar wages, the USA improved from 1933, onward. More men were working and more men had money.

The popular depiction of the Great Depression has been that it was “ended†by the Second World War. The recovery for the USA was actually nearly complete by the time America entered that conflict. Likewise, it is almost a truism that shared hardship can bring forth fraternity, but the Great Depression was, itself, a trauma, one that spread throughout the USA. While America’s World War experience in the 1940s certainly cemented matters, the Great Depression likely had as much of a social effect as did the war. That is, the “GI hypothesis†overstates the effect of military service and ignores other economic and social factors. This is not to deny any effect of shared military service. Without the war experience, the collapse of 1946 may have happened earlier.

Alternatively, while bonds forged during economic and social rebuilding from the Great Depression may have been stabilizing, the effects of the post-war economic boom were highly destabilizing for the USA. That is to say, the economic recovery of the USA essentially required building communities—restoring the daily business of life. The World War experience threw men together in crisis, then removed the crisis. Once the crisis was gone, the primary motivation for camaraderie was also gone. The daily business of life quickly assumed more importance than did the military experience. Even contemporary entertainment of the day noticed this post-war trend, such as Irving Berlin's White Christmas.

The Great Recovery is followed by the Great Complacency. During this era (1946–1961), things looked excellent, but only on the surface. The number of Master Masons was increasing to unprecedented levels (so long as one ignored the total size of the USA’s population). Membership levels only improving (so long as one ignored the fact that rates of change were already in extremely steep decline). Freemasonry in the USA was building ever-larger institutional charities and having an unprecedented social impact—this time free of the strident anti-masonry of the Know Nothings era. However, as has already been mentioned, decline had set in before it was immediately visible. The rate of membership change started dropping after 1946, and it fell nearly as rapidly as at any other time in the period studied.

The model I present precludes many hypotheses to explain the decline in Masonic membership. First, if the “rot at the root†actually began before the 1950s, any model based on social changes that occurred in that or a later decade cannot be valid. Post-1950s cultural upheavals may have contributed to the decline (but see the “Moribund Stagnationâ€, herein), but they could not have initiated it. The cause of a disorder cannot occur after the disorder. Thus any hypothesis to explain the Great Decline will have to look at Freemasonry and society in the late 1940s and early 1950s, right in the middle of the conventially-accepted “golden ageâ€. What did Freemasonry do at that point that it had not done before? How did it change, and how did it respond to changes in American society. Such questions require more in-depth knowledge of the history of American Freemasonry than I have, but other authors with the requisite knowledge have proposed potentially workable hypotheses, although their hypotheses are based on the more conventional chronology.

The Great Complacency is followed by the Moribund Stagnation. This period (1961–1993) is the era in which Freemasonry visibly declined by any measure of decline. Total Master Masons declined; Master Masons vs. population declined; and the rate of change was relentlessly negative. However, it was also relentlessly constant. That is, while membership was in constant decline, the rate of decline did not change. This calls into question those models that indulge in denunciation of the 1960s as a time when all things good were destroyed, an unfortunately popular pastime among men over a certain age. Freemasonry did decline, but it appears to have coasted in decline. Whatever mechanisms that harmed Freemasonry were already strongly in place by 1961. If the 1960s truly were such a time of disastrous upheaval for Freemasonry, then decline in numbers should not have been so constant. Instead, it would have been marked by ever-snowballing collapse, as was seen during the Great Complacency of the 1950s. If anything, the 1950s was when any dysfunction would have entered the Craft, since it was when the second collapse began.

What happened in the 1960s is more reminiscent of a lingering illness rather than a catastrophe. However, since the decline is superficially visible starting in 1960, the 1960s and later eras are, somewhat blindly, given the blame. No consideration is made of the possibility that what happened on the surface in the 1960s and afterwards may be the product of earlier deep trends.

The final period, “Recovery?†could be viewed with cautious optimism. While both absolute and population-adjusted numbers of Master Masons still is declining, the rate of decline has slowed and continues to slow on an annual basis. Indeed, if this trend continues, the possibility exists that numbers of Master Masons could begin to rise by as early as 2022, although this would be an optimistic extrapolation. In essence, something appears to have happened in the early 1990s that may have reversed a generation’s downward spiral, although any reversal is very modest.

Where to go from here? I am not a mover or shaker, but my model is something that others with far more knowledge and influence could potentially use for the good of the Craft in the USA.

The total number of Master Masons (Fig. 1) appears to show that Freemasonry in the USA reached a high point in 1959 and has been declining ever since. Such a presentation, although popular, is quite deceptive, since the US population was also increasing at a great rate in the decades immediately after the Second World War.

Thus, when adjusting for population (Fig. 2), the result presents a different picture. Freemasonry had its highest population-adjusted membership (within the years surveyed) in 1927, with a temporary reversal of losses that ended in 1959 but never made its way back up to former levels. This difference between raw counts and population-adjusted counts may, in and of itself, be important, since it suggests that nostalgia for “glory days†of the 1950s may actually be ill-founded. What is more informative than counts if we are looking at membership trends is how membership changes. That is, the slope of the membership curve.

Differentiating the population-adjusted figures finds rates of change (slopes of the curve) in membership (Fig. 3). The differentiation result is particularly informative.

The various inflections, combined with more raw membership data, suggest the possibility of dividing 20th and early 21st century Freemasonry in the USA into five periods (Fig. 4). The first of these I call the "Great Collapse". Freemasonry in the USA had its fastest rate of loss, without exception, at least for the period covered. This was followed by the "Great Recovery", in which the losses of the Great Collapse began to be reversed almost as fast as they had occurred. The next period I call the "Great Complacency". On the surface, merely looking at raw counts of Master Masons, things looked great. There was nothing to worry about. However, looking a little deeper showed that Freemasonry's penetration into the population of the USA as a whole had never returned to pre-Great Depression levels, and looking at the rates of change for Master Masons per population showed that much of the "golden age" was actually a time of loss of growth that linearly slid into decline almost as extreme as the decline of the Great Collapse. The long period after the Great Complacency I call "Moribund Stagnation". That is, while Freemasonry was in a state of decline, the rate of decline was at least constant instead of getting progressively worse, year after year. Finally, the possibility of a "Recovery?" may be present in the data. Although counts of Master Masons and of Master Masons per population still drop annually, the rate at which they drop has been growing less severe.

To look at these phases in more detail, It is true that freemasonry in the USA has been in unremitting membership decline (slope less than zero) for several decades, but actual decline (slope less than zero) in terms of Master Masons vs. population began in 1955, four years before the highest raw count of Master Masons was achieved. What is also noteworthy are four inflection points in the slopes, occuring at 1933, 1946, 1961, and 1993. In 1933, the Great Decline reversed itself. Matters improved from 1933 to 1946, when membership decline rapidly slowed and then reversed to growth. However, in 1946, the trend underwent another drastic reversal.

The year 1946 had the greatest increase of Master Masons, but things went downhill from that point, onward. The trend sharply declined, even if the numbers and population-adjusted numbers still increased. In essence, the “glory days†of 20th century Freemasonry were actually little more than a few years, 1941–1946, when numbers were growing and the growth trend was not plummeting. What is interesting is that this does not mesh well with many current hypotheses to explain changes in membership. The conventional explanation for membership drops and gains in Freemasonry of the early 20th century has been that the Great Depression drove men away from the Craft, and this was reversed when GIs coming home after the war sought to continue their military comaraderie. In actuality, watever early-century decline in Masonic membership began before the stock market crash of 1929 and had reversed itself after 1933. Freemasonry had already been recovering for several years before the USA entered the Second World War. Growth was almost explosive throughout the war, but the the trend catastrophically reversed by 1946. Residual effect produced gains in both numbers and population-adjusted numbers, but growth had begun to decline before the 1950s had even started and slipped into decline by 1955. Thus, whatever had driven the amazing resurgence of American Freemasonry in the middle of the 20th century was already half a decade gone when the 1950s had started.

In 1961, the precipitous collapse of Freemasonry essentially ended, replaced by a relatively constant state of decline, in which the Craft essentially coasted downhill. It would not be unreasonable to propose that nothing done between 1961 and 1993 had any significant effect for good or ill on Craft participation. Freemasonry in the USA had settled into a state of steady decay, as constant as a radioactive half-life. Around 1993, the trend appears to have once again reversed, although far more moderately than before. Instead of the constant rate of loss that had been the regime for the previous generation, nationwide rate of loss of Master Masons (population adjusted) began to ease. By 2010, the rate of loss had dropped to about one third the loss rate of the stagnation generation (1961–1993).

Conventional models of “what worked†for Freemasonry in the 20th century may very well be entirely wrong. First, the period of greatest growth began before the USA had entered the Second World War. This period ended a year after the war. By the time the majority of GI Generation Master Masons had been elevated, decline had already set in, even if it was not superficially apparent. The 1950s was not a golden age, it was merely gilded. While Freemasonry became “largerâ€, under the surface it was drastically already in decline. By the time the 1960s appeared, the Craft in the USA had essentially entered a holding pattern, sustained in a constant downward spiral.

Whatever brought men into Freemasonry in the early 20th century was already in place in the USA before any enforced camaraderie of the Second World War. Large numbers of men were also inducted into the military for the Korean and Viet Nam conflicts, but these eras did not see even tiny spikes in Master Masons. The “GI hypothesis†simply does not fit deeper analysis of the data. It is not doubted that shared hardship can create fraternity. However, it is also an unfortunately common presumption that nothing in history is important except warfare. Thus, we are taught to classify American history by our wars, as if nothing else important ever happens in the USA other than warfare.

Shared American hardship in the early 20th century did not begin in December of 1941. An even deeper shared trauma began in 1929. This refers, of course, to the Great Depression. This was a shared experience that overturned our entire culture and led to mass cooperative efforts that essentially set the stage for what the USA was able to do during the Second World War. Thus, in opposition to the “GI hypothesisâ€, a more prosaic social and economic hypothesis could be considered. The year 1933 marks the low point of the Great Depression in the USA. In terms of both gross domestic product per person, employment, and real-dollar wages, the USA improved from 1933, onward. More men were working and more men had money.

The popular depiction of the Great Depression has been that it was “ended†by the Second World War. The recovery for the USA was actually nearly complete by the time America entered that conflict. Likewise, it is almost a truism that shared hardship can bring forth fraternity, but the Great Depression was, itself, a trauma, one that spread throughout the USA. While America’s World War experience in the 1940s certainly cemented matters, the Great Depression likely had as much of a social effect as did the war. That is, the “GI hypothesis†overstates the effect of military service and ignores other economic and social factors. This is not to deny any effect of shared military service. Without the war experience, the collapse of 1946 may have happened earlier.

Alternatively, while bonds forged during economic and social rebuilding from the Great Depression may have been stabilizing, the effects of the post-war economic boom were highly destabilizing for the USA. That is to say, the economic recovery of the USA essentially required building communities—restoring the daily business of life. The World War experience threw men together in crisis, then removed the crisis. Once the crisis was gone, the primary motivation for camaraderie was also gone. The daily business of life quickly assumed more importance than did the military experience. Even contemporary entertainment of the day noticed this post-war trend, such as Irving Berlin's White Christmas.

The Great Recovery is followed by the Great Complacency. During this era (1946–1961), things looked excellent, but only on the surface. The number of Master Masons was increasing to unprecedented levels (so long as one ignored the total size of the USA’s population). Membership levels only improving (so long as one ignored the fact that rates of change were already in extremely steep decline). Freemasonry in the USA was building ever-larger institutional charities and having an unprecedented social impact—this time free of the strident anti-masonry of the Know Nothings era. However, as has already been mentioned, decline had set in before it was immediately visible. The rate of membership change started dropping after 1946, and it fell nearly as rapidly as at any other time in the period studied.

The model I present precludes many hypotheses to explain the decline in Masonic membership. First, if the “rot at the root†actually began before the 1950s, any model based on social changes that occurred in that or a later decade cannot be valid. Post-1950s cultural upheavals may have contributed to the decline (but see the “Moribund Stagnationâ€, herein), but they could not have initiated it. The cause of a disorder cannot occur after the disorder. Thus any hypothesis to explain the Great Decline will have to look at Freemasonry and society in the late 1940s and early 1950s, right in the middle of the conventially-accepted “golden ageâ€. What did Freemasonry do at that point that it had not done before? How did it change, and how did it respond to changes in American society. Such questions require more in-depth knowledge of the history of American Freemasonry than I have, but other authors with the requisite knowledge have proposed potentially workable hypotheses, although their hypotheses are based on the more conventional chronology.

The Great Complacency is followed by the Moribund Stagnation. This period (1961–1993) is the era in which Freemasonry visibly declined by any measure of decline. Total Master Masons declined; Master Masons vs. population declined; and the rate of change was relentlessly negative. However, it was also relentlessly constant. That is, while membership was in constant decline, the rate of decline did not change. This calls into question those models that indulge in denunciation of the 1960s as a time when all things good were destroyed, an unfortunately popular pastime among men over a certain age. Freemasonry did decline, but it appears to have coasted in decline. Whatever mechanisms that harmed Freemasonry were already strongly in place by 1961. If the 1960s truly were such a time of disastrous upheaval for Freemasonry, then decline in numbers should not have been so constant. Instead, it would have been marked by ever-snowballing collapse, as was seen during the Great Complacency of the 1950s. If anything, the 1950s was when any dysfunction would have entered the Craft, since it was when the second collapse began.

What happened in the 1960s is more reminiscent of a lingering illness rather than a catastrophe. However, since the decline is superficially visible starting in 1960, the 1960s and later eras are, somewhat blindly, given the blame. No consideration is made of the possibility that what happened on the surface in the 1960s and afterwards may be the product of earlier deep trends.

The final period, “Recovery?†could be viewed with cautious optimism. While both absolute and population-adjusted numbers of Master Masons still is declining, the rate of decline has slowed and continues to slow on an annual basis. Indeed, if this trend continues, the possibility exists that numbers of Master Masons could begin to rise by as early as 2022, although this would be an optimistic extrapolation. In essence, something appears to have happened in the early 1990s that may have reversed a generation’s downward spiral, although any reversal is very modest.

Where to go from here? I am not a mover or shaker, but my model is something that others with far more knowledge and influence could potentially use for the good of the Craft in the USA.